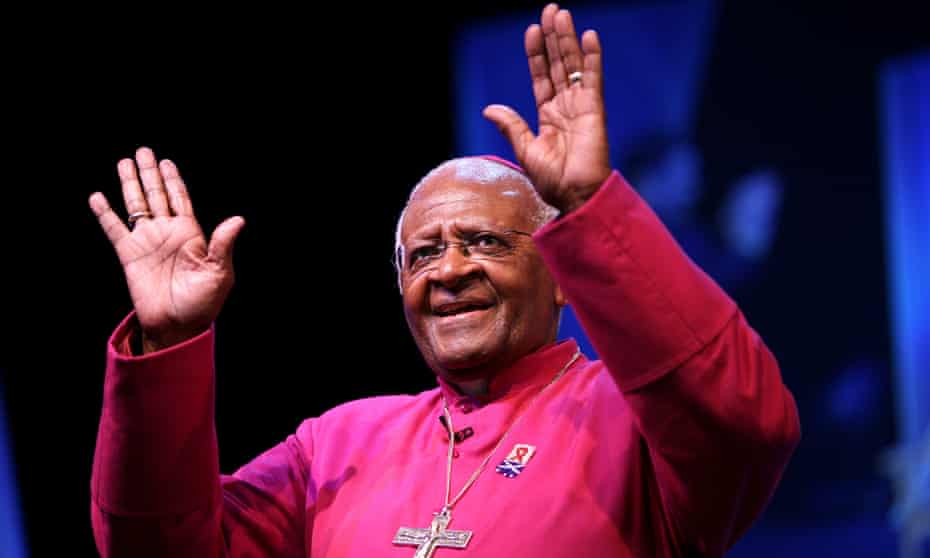

South Africa set for battle over legacy of ‘moral compass’ Desmond Tutu

"From the moment he resigned from his post as a schoolteacher rather than comply with the orders of the racist, repressive apartheid regime in South Africa in 1958, Desmond Tutu never deviated from his principles, fighting for tolerance, equality and justice at home and abroad. This brought him love, influence and a moral prestige equalled by few others on the African continent or beyond.

But Tutu, the cleric and activist who died on Sunday in Cape Town aged 90, was not just outspoken in support of the causes he felt to be right – such as LGBT rights – but a fierce and implacable opponent of what he felt to be wrong. Criticism was often tempered with humour. On occasion, it was delivered straight. This earned him enemies, and still does.

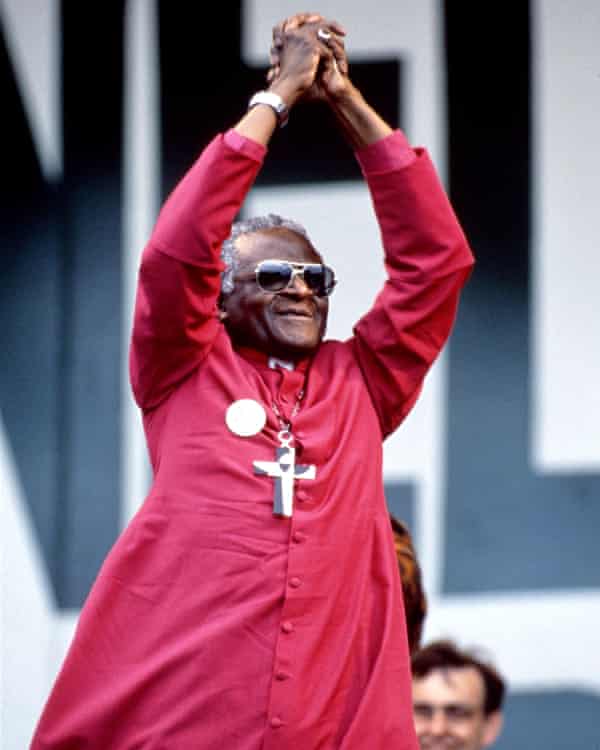

Tutu’s first and most famous enemy was the apartheid system that prevailed in his homeland from 1948. Fully engaged in the freedom struggle from the late 1970s, Tutu was a key figure in telling the rest of the world about the grievances of South Africa’s exploited majority communities. The cleric and activist, branded a “rabble-rouser” by authorities, did not pull his punches. Apartheid was as bad as “nazism”, he told the United Nations in 1988, adding that politicians in the west who failed to support sanctions campaigns against the regime in Pretoria were racists.

“We don’t want to drive the white people into the sea, we don’t want to destroy white people,” said Tutu, who won the Nobel peace prize in 1984 for his nonviolent efforts to end apartheid and avoid devastating conflict in South Africa. “But is it too much to ask that in the land of our birth, we walk tall as human beings made in the image of God? … To say we want to be free?”

In a letter, Tutu, then head of the South African Council of Churches, informed Margaret Thatcher in 1984 that a British invitation to the South African prime minister to visit the UK was “a slap in the face of millions of black South Africans who are the daily victims of one of the most vicious policies in the world”.

But he did not spare those in power in the “rainbow nation” that emerged after South Africa’s first free election in 1994. The phrase was his own, and set up aspirations that were never fulfilled. A decade later, Tutu gave a high-profile lecture in which he listed the many achievements of his countrymen under democracy but implied that many came despite their new political rulers who sought their own advancement before that of the poor. “What is black empowerment when it seems to benefit not the vast majority but a small elite that tends to be recycled? Are we not building up much resentment that we may rue later? We are sitting on a powder keg,” Tutu said.

The Nobel laureate’s criticism of the ruling African National Congress party became even harsher during the tenure of President Jacob Zuma, which ended in 2018 amid allegations of systematic corruption and maladministration. Relations between the ANC and Tutu improved slightly after Cyril Ramaphosa, a former labour activist and tycoon who has sought to bring in moderate reform and fight graft, took power.

Ramaphosa’s tribute on Sunday, with its reference to the passing of “a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa”, underlines the general sense of disillusionment with their successors and it will be the Anglican church, not the government, that will organise the former archbishop’s funeral, according to Covid restrictions as South Africa battles its fourth wave of infections.

Even now, some Zuma loyalists have distanced themselves from the outpouring of grief and tributes. One reason is the memory of the cleric’s rigorous and personally harrowing leadership of South Africa’s truth and reconciliation commission, which investigated apartheid-era crimes to bring closure to victims and the nation. Tutu’s commitment and determination did not just anger supporters of the white officials constrained to disclose the depredations of the apartheid regime. The council’s investigation of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Nelson Mandela’s former wife, for the abduction and eventual murder of a teenager still rankles. On social media on Sunday, some called Tutu a “stooge for white people”.

In reality, Tutu took aim at exploiters and autocrats anywhere he found them. Justly lauded as an icon of nonviolent activism, he enraged those who prefer less pacific means to effect change or hold on to power. Robert Mugabe, the former dictatorial leader of Zimbabwe, resorted to insults to counter Tutu’s cutting words, calling their author “an angry, evil and embittered little bishop”.

Such sentiments did not bother the smiling, chuckling, charismatic cleric – though Tutu confessed to one interviewer that he “loved to be loved”. Even in the Anglican church, an institution to which he dedicated much of his life, Tutu’s liberal understanding of faith riled many. No one doubted his faith or commitment to the institution but not every cleric enjoyed hearing about a God who had a “soft spot for sinners” and fewer still on a continent riven by visceral homophobia appreciated his vocal, consistent support for LGBT rights.

“I would not worship a God who is homophobic and that is how deeply I feel about this,” he said in 2013. “I would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven. No, I would say, ‘Sorry, I would much rather go to the other place.’” He also supported the right to assisted death, another controversial position within the church. Other interventions argued for urgent action against climate change and a change in US policy on Israel.

Right to the end Tutu was “on the side of the angels”, as one resident of a township not far from where the archbishop lived and died said on Sunday.

In one of his last public appearances, aged 89, he received a Covid vaccine, an important statement in a country that has lost up to 250,000 lives to the pandemic out of a population of 59m, according to excess mortality figures, and suffers from widespread vaccine hesitancy.

Analysts predict a battle over Tutu’s legacy as South African political factions jostle to claim they are the true heirs of “the Arch”, as he was familiarly known. For the moment though, there is profound grief at the loss of the country’s “moral compass” and a genuine sense of bereavement.

“South Africa and the world has lost one its greatest parents and role models. [Tutu] was abnormally imbued with a sense of pastoral duty to serve the best interests of his species – the human family – and planet,” a statement from the office of the archbishop of Cape Town said. “To do the right thing. To make people feel part. To advance justice, humanness, peace and joy … His work is not done; it is in our hands now.”

No comments:

Post a Comment