A collection of opinionated commentaries on culture, politics and religion compiled predominantly from an American viewpoint but tempered by a global vision. My Armwood Opinion Youtube Channel @ YouTube I have a Jazz Blog @ Jazz and a Technology Blog @ Technology. I have a Human Rights Blog @ Law

Wednesday, December 31, 2025

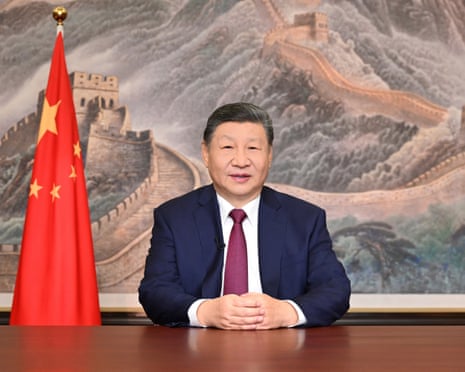

Xi Jinping vows to reunify China and Taiwan in New Year’s Eve speech | China | The Guardian

Xi Jinping vows to reunify China and Taiwan in New Year’s Eve speech

"Reunification ‘is unstoppable’, says Chinese president, a day after the conclusion of intense military drills

China’s president, Xi Jinping, has vowed to reunify China and Taiwan in his annual New Year’s Eve speech in Beijing.

Speaking the day after the conclusion of intense Chinese military drills around Taiwan, Xi said: “The reunification of our motherland, a trend of the times, is unstoppable.”

China claims Taiwan, a self-governing island, as part of its territory and has long vowed to annex it, using force if necessary.

US intelligence is increasingly concerned about the advancing capabilities of China’s armed forces to launch such an attack if Xi decides the time is right.

On Monday and Tuesday, China’s People’s Liberation Army launched live-fire military drills around Taiwan, simulating a blockade of main ports and sending its navy, air force, rocket force and coastguard to encircle Taiwan’s main island. The drills, called “Justice Mission 2025”, came closer to Taiwan than previous exercises, and involved at least 89 warplanes, the highest tally for more than a year.

The drills were expected by analysts before the year’s end but were also connected by Chinese commentators to a recent arms approval by the US government for a record $11bn (£8bn) weapons sales to Taiwan.

Speaking in Beijing on Wednesday evening, Xi said China “embraced the world with open arms” and highlighted several multilateral conferences hosted by Beijing this year, including the Shanghai Cooperation Summit in August, when world leaders including Russia’s Vladimir Putin, India’s Narendra Modi and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, gathered in Tianjin, a port city near Beijing.

The broadcast of Xi’s speech on Chinese state media was interspersed with several shots of China’s largest ever military parade, which was held in September to mark 80 years since the end of the second world war. During the parade, which was viewed as an unbridled display of military force, Xi, Putin and North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong-un, stood side by side in Beijing – a geopolitical alignment that has been called the “axis of upheaval”.

Central to Xi’s vision of a new world order is the annexation of Taiwan and the support of other countries in recognising Taiwan as part of “One China” ruled by the Chinese Communist party in Beijing, something that the majority of Taiwanese people reject.

In his speech, Xi also highlighted “Taiwan Retrocession Day”, a memorial day created in 2025 to mark the anniversary of the end of Japanese imperial rule in Taiwan in 1945. This year, Taiwan also passed a law to recognise the date, 25 October, as a national holiday. The legacy of the second world war has been a big theme in political rhetoric in China and Taiwan this year. China has emphasised its role in defeating the Japanese in that conflict, something that China feels has been underappreciated in the west. Taiwan’s president, Lai Ching-te, gave a punchy speech this year comparing Taiwan to European democracies in the 1930s that faced a threat from Nazi Germany.

Xi’s speech also praised China’s progress in hi-tech development this year, mentioning kickboxing robots and Tianwen-2, a comet exploration mission that launched in May. He also flagged the global success of Chinese cultural exports, such as the video game Black Myth: Wukong and the animated film Ne Zha 2.

Earlier in the day, Xi addressed a meeting of top Chinese Communist party officials and said that China was on track to meet its 5% GDP growth target."

Xi Jinping vows to reunify China and Taiwan in New Year’s Eve speech | China | The GuardianIsraeli ban on aid agencies in Gaza will have ‘catastrophic’ consequences, experts say | Gaza | The Guardian

Israeli ban on aid agencies in Gaza will have ‘catastrophic’ consequences, experts say

"Thirty-seven NGOs told they have to cease operations, putting Palestinian lives ‘at imminent risk’

Israel’s new ban on dozens of aid organisations working in Gaza will have “catastrophic” consequences for the delivery of vital services in the devastated territory and will put Palestinian lives “at imminent risk”, diplomats, humanitarian workers and experts say.

Thirty-seven NGOs active in Gaza were told by Israel’s ministry of diaspora affairs on Tuesday that they would have to cease all operations in the territory within 60 days unless they fulfilled stringent new regulations, which include the disclosure of personal details of their staff.

In a statement, the ministry said the measures were intended to prevent NGOs employing staff with links to extremist organisations and were necessary to ensure that Hamas did not exploit international aid.

Israel has repeatedly claimed that Hamas has systematically diverted aid supplies for military or political purposes and infiltrated aid organisations but has provided limited evidence to support the allegations.

Aid organisations said they had been engaging with Israeli officials for many months.

“We have made strenuous efforts to comply even if these demands are made nowhere else. We do extensive vetting ourselves. It would be disastrous for us to have any armed combatants or people linked to armed groups among our staff,” said Athena Rayburn, executive director of the Association of International Development Agencies, which represents more than 100 NGOs operating in Gaza and the occupied West Bank.

“We have such strong measures in place already and have proposed alternatives to the Israeli authorities that would meet this requirement, and they have refused.”

Israeli officials said that the NGOs hit by the ban only supplied 15% of the desperately needed assistance in Gaza, which is suffering an acute humanitarian crisis after two years of devastating war.

Aid officials said this calculation was misleading because most of the NGOs affected by the ban did not deliver their own services but were contracted by the UN to run basic health clinics, malnutrition screening, hygiene and shelter support and much else.

One senior UN official said the ban would “cripple” relief operations. Israeli laws banning Unrwa, the main UN agency dealing with Palestinians, from Gaza had already had a significant impact, they added.

Rayburn said the ban would bring about a “catastrophic collapse of humanitarian services”, and that Israel authorities had been made “fully aware” of potential consequences.

Under the 20-point agreement that allowed a fragile ceasefire to come into effect in October, Israel is obliged to allow “full aid” to be “immediately sent into Gaza”.

The ceasefire ended two years of relentless conflict, but further progress towards a lasting peace deal has stalled, with Israel saying it will not withdraw from the 53% of Gaza territory that is still under its control until Hamas disarms and returns the remains of the last hostage it is holding. The Islamist militant organisation has so far refused to commit to full disarmament.

Speaking on Monday, Donald Trump said he hoped “reconstruction” could begin soon in the Palestinian territory, reduced to ruins by Israeli offensives in response to Hamas’s 7 October 2023 attacks, but gave no details.

Some aid officials said they would be able to find “workarounds” to mitigate the worst effects of the ban but that urgent assistance was needed in Gaza, where recent storms have destroyed tents that were the only shelter for an estimated 500,000 people, food is expensive and clean water, scarce.

On Wednesday, Volker Türk, the UN human rights chief, said in a statement that Israel’s move was “outrageous”, warning that “such arbitrary suspensions make an already intolerable situation even worse for the people of Gaza”.

The EU warned on Wednesday that the new NGO registration law that had led to the ban “cannot be implemented in its current form”.

But Israeli officials insisted the law was necessary. “They [the NGOs] refuse to provide lists of their Palestinian employees because they know, just as we know, that some of them are involved in terrorism or linked to Hamas,” Gilad Zwick, spokesperson for the ministry of diaspora affairs and combating antisemitism, told AFP.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the main medical aid organisation, is among those facing a ban.

Israeli officials claim individuals affiliated with MSF have links to Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad. MSF rejects the accusations as unsubstantiated, adding it would never knowingly employ anyone engaged in military activity.

Shaina Low, a spokesperson for the Norwegian Refugee Council, which has extensive operations in Gaza, said it would be impossible to fulfil the new Israeli requirements.

“It is a security concern and a legal concern … and it’s all a distraction from actually getting aid to the people who need it,” she said.

In May, aid agency Oxfam said the requirement to share staff details raised protection concerns, after attacks on humanitarian workers in Gaza.

Several aid officials reported that during the war in Gaza they had been asked by Israeli military officials to supply details of the whereabouts of their international staff there. Suspecting that the information would be used to allow Israeli strikes on offices where there were only Palestinian staff, the NGO refused.

After targeting Unrwa last year, Israel and the US backed the Gaza Humanitarian Fund, a private company that distributed aid from a small number of hubs in southern Gaza amid chaotic conditions that led to the death from Israeli fire of more than 1,000 people.

Cogat, the Israeli agency charged with administration of Gaza, said 4,200 aid trucks would continue to enter every week via the UN, donor countries, the private sector, and more than 20 international organisations that have been reregistered.

The Hamas raid that triggered the war in Gaza killed 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and led to the abduction of 250. The ensuing Israeli offensive killed about 70,000, mostly civilians, with hundreds more killed since the ceasefire."

Opinion | Trump Spent the Past Year Trying to Crush Dissent - The New York Times

I Counted Trump’s Censorship Attempts. Here’s What I Found.

By Nora Benavidez

"Ms. Benavidez is the senior counsel for the media policy organization Free Press.

“We took the freedom of speech away.”

That was part of President Trump’s explanation in October of his executive order that purports to criminalize burning the American flag. Though his words fail as a constitutional rationale, they inadvertently distill many of his efforts at smothering dissent during the past 11 months.

Since returning to office, Mr. Trump and his administration have tried to undermine the First Amendment, suppress information that he and his supporters don’t like and hamstring parts of the academic, legal and private sectors through lawsuits and coercion — to flood the zone, as his ally, Steve Bannon, might say.

Some examples are well known, such as when ABC briefly took Jimmy Kimmel off the air after Brendan Carr, the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, objected to a reference in one of Mr. Kimmel’s monologues about the killing of Charlie Kirk. Other examples received less attention, but by my count, this year there were about 200 instances of administration attempts at censorship, nearly all of which I outline in a new report.

Mr. Trump’s playbook isn’t random. It employs several recurring modes of attack.

The president has tried to cow the press. His administration banned Associated Press reporters from certain parts of the White House and Air Force One because the outlet uses “Gulf of Mexico” rather than the term Mr. Trump prefers, “Gulf of America.” It tried and failed to force some of the nation’s biggest news organizations to agree to restrictions on coverage of the Pentagon. He has said critical coverage of his initiatives is “really illegal.”

A journalist from El Salvador, Mario Guevara, was arrested while reporting on a No Kings protest in Georgia; he was detained for more than three months, then deported. At an Oval Office meeting between Mr. Trump and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, an ABC News correspondent, Mary Bruce, asked about the killing of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi and about the Jeffrey Epstein files. Mr. Trump replied by berating her at length, at one point describing one of her questions as “insubordinate” — a characterization that upends the entire notion of a free press.

Sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter Get expert analysis of the news and a guide to the big ideas shaping the world every weekday morning.

The administration has used immigration status to try to suppress political speech. In March, Mahmoud Khalil, a green card holder and a leader of pro-Palestinian demonstrations on the Columbia campus, was arrested and detained by immigration officials for several months. That month, Rumeysa Ozturk, a student visa holder, was arrested by immigration officials and detained for several weeks, apparently because she was an author of an opinion essay criticizing Tufts University for its response to the Israel-Hamas war.

It seems almost no one is beyond the scope of administration efforts to muzzle views or decisions that conflict with Mr. Trump’s agenda: After Federal District Court Judge James Boasberg ruled against the administration in a case involving the deportation of Venezuelans to El Salvador, Mr. Trump called for the judge to be impeached. A trainee was dismissed from the F.B.I.’s academy, apparently for having displayed an L.G.B.T.Q. Pride flag. The F.B.I. also appears to have fired agents for kneeling during George Floyd protests.

At a news conference in Tampa, Fla., Kristi Noem, the secretary of homeland security, asserted that filming Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers while they are in the field is tantamount to violence. In Los Angeles, Senator Alex Padilla, Democrat of California, was forced to the ground and handcuffed after interjecting at a news conference held by Ms. Noem.

In just the past few days, the administration has banned a former member of the European Commission and four European researchers from the United States, claiming that their efforts to fight disinformation and hate speech online amount to censorship of Americans.

The president federalized and deployed the National Guard in Los Angeles; a federal appeals court found that his administration had illegally prolonged the deployment. He similarly sent the National Guard to the Chicago area — an action that the Supreme Court, for now, has blocked.

As part of the administration’s war on so-called wokeness, it has identified hundreds of words, with the intent of curtailing their use. Mr. Trump issued an executive orderdirecting staff members at national parks and museums to get rid of content that, he says, portrays America “in a negative light.” Just two days after Inauguration Day, the Justice Department’s chief of staff sent a memo calling for a “litigation freeze” in the department’s civil rights division.

Two of Mr. Trump’s perceived political adversaries — James Comey, a former F.B.I. director, and Letitia James, the New York attorney general — were criminally charged (in cases now both dismissed) that were difficult to see as anything other than revenge prosecutions. A few days into his term, the president fired more than a dozen inspectors general from various federal government agencies.

Some of the nation’s biggest law firms — including Paul, Weiss and Kirkland & Ellis — have caved under presidential pressure and signed deals agreeing to contribute pro bono work for causes dictated by the administration. Several prestigious universities submitted to agreements in which they committed to change certain policies and, in some cases, pay what amounts to millions of dollars in fines.

Mr. Trump has sued social media platforms for their content moderation policies — free-speech decisions, in other words — leading to Meta, X and YouTube capitulating through settlements totaling around $60 million.

These examples are just a sampling from the administration’s relentless campaign to stifle dissent. What is important to recognize is that these efforts work in concert in their frequency and their volume: Even the most egregious cases seem to quickly fade from public consciousness, and in that way, they’re clearly meant to overwhelm us and make us t"hink twice about exercising our rights.

Over the past year, individual and communal acts of resistance have blunted the potency of Mr. Trump’s censorship campaign and contributed to his declining approval ratings. Unquestionably, more and more Americans are rejecting his overreach.

But constitutional rights and democratic norms don’t disappear all at once; they erode slowly. The next three years will require a vigilant defense of free speech and open debate."

More than 75% of US adults may meet criteria for obesity under new definition: Study

More than 75% of US adults may meet criteria for obesity under new definition: Study

“A new study suggests that using waist-based measurements, in addition to BMI, could nearly double the prevalence of obesity in US adults, from 40% to over 75%. The study highlights the limitations of BMI as a standalone tool and emphasizes the need for improved obesity detection methods. While the new definition may raise current obesity estimates, further research is needed before widespread adoption.

For decades, doctors have relied on body mass index (BMI) -- a tool that uses height and weight to estimate body fat -- to determine obesity.

A team of researchers from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard University, Yale University and Yale New Haven Health, found that BMI alone may significantly underestimate how many U.S adults have obesity.

Using a new definition that includes waist-based measurements, the team found that more than 75% of adults may meet criteria for obesity compared to 40% when using BMI alone.

Stock photo of a person measuring their waist.

Kinga Krzeminska/STOCK PHOTO/Getty Images

Earlier this year, The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology Commission -- a partnership between the medical journal and the health clinic King's Health Partners Diabetes, Endocrinology and Obesity -- proposed a revised obesity definition that included waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and waist-to-height ratio.

More than 70 medical organizations around the world have endorsed the definition but its use in practice has not been evaluated, according to the study authors.

"BMI is the standard measure for determining criteria for obesity. It's the most widely known metric," Dr. Erica Spatz, a cardiologist at Yale School of Medicine and co-author of the new study, told ABC News.

She noted that BMI alone does not account for adipose tissue, which stores energy, insulates organs and produces hormones that regulate appetite.

Spatz said adipose tissue is less visible than other types of fat but "is more associated with high blood pressure, diabetes and heart disease."

For the study, published in JAMA Network Open, the team used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, a national survey run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that measures the health and nutrition of adults and children in the U.S.

The team looked at data from more than 14,000 participants representing 237.7 million adults between 2017 and 2023, applying the Lancet Commission's proposed obesity criteria along with BMI.

They found an estimated 75.2% of U.S. adults met criteria for obesity using BMI and additional body measurements compared to 40% when BMI alone was reviewed.

Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford, an associate professor of medicine and pediatrics at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in the study, told ABC News that the findings provide a sense of how significant obesity is in the U.S.

"We do have a major problem. Obesity is by far the most significant chronic disease in human history," she said. "And this Lancet Commission really gives us a sense of how significant it is and how much we need to be doing a better job of treating it, make sure that we have the clinicians that are trained to identify not only obesity itself, but the over 230 chronic diseases associated with it and making sure that we have a healthier society."

Nearly four in 10 adults with a "normal" BMI were found to have excess body fat when waist-based measures were also applied.

The study also found that obesity prevalence increased sharply with age and was higher among Hispanic adults though rates were similar between men and women.

The authors noted that the study has limitations. And because nearly all adults age 50 and older were classified as having obesity under the new definition, age-specific thresholds are needed as well.

The authors did highlight the limitations of BMI as a standalone screening tool and suggest that incorporating waist measurements could improve obesity detection.

They also stressed that because the new criteria will likely raise the current obesity estimates, more research should be done before broadly adopting the new definition.

ABC News' Dr. Veronica Danquah contributed to this report.

Crystal Richards, MD, MS is a pediatric resident doctor at New-York Presbyterian Hospital Columbia University Medical Center and a member of the ABC News Medical Unit.”

Tuesday, December 30, 2025

NPR’s C.E.O. Was a Right-Wing Target. Then the Real Trouble Started.

NPR’s C.E.O. Was a Right-Wing Target. Then the Real Trouble Started.

"Katherine Maher has taken an unyielding approach to NPR’s biggest battles — which has sometimes put her at odds with her colleagues in public media.

Katherine Maher, the chief executive of NPR, has dealt with plenty of criticism this year. Did she consider quitting? “I really don’t like bullies,” she said.Jason Andrew for The New York Times

This year, Benjamin Mullin has covered the effects of the elimination of federal funding on NPR, PBS and local stations across the country.

Katherine Maher knew that running NPR was going to be difficult. But since taking over as chief executive last year, she has confronted one crisis after another.

Right-wing activists dredged up her old posts on social media and tried to get her fired. Congress stripped more than $500 million in annual funding from public media.

She has become a target not just of NPR’s traditional opponents on the political right but of some within the tightknit world of public broadcasting, who wanted her to take a more pragmatic tack. At one point, the chief executive of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, one of NPR’s biggest supporters, told Ms. Maher she should quit.

Her predecessors were accused of bringing a tote bag to a knife fight during political attacks on the organization. Ms. Maher, by contrast, has been more aggressive, refusing to compromise with Congress and taking the Trump administration to court, along with a key ally.

Ms. Maher, 42, stood by her strategy.

“The government targeted public funding to punish specific editorial decisions it disagreed with,” she said in a recent interview with The New York Times. “That’s not a funding dispute dressed up as a constitutional case; that’s textbook First Amendment retaliation.”

Ms. Maher’s stance brought support pouring in for her organization. NPR emerged from the biggest political battle in its history on firm footing, generating record donations.

But the loss of roughly $500 million from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting has been devastating for other parts of the public media universe. Many local stations, which pay dues to NPR and PBS, are laying off employees.

In other words, Ms. Maher and NPR have managed to hold on to their influence over public broadcasting this year, even as that system was dealt a terrible blow and is far weaker overall. Yet there are emerging challenges to NPR’s sway over public radio. In the wake of the funding fight, a coalition of public media organizations has teamed up to form Public Media Infrastructure, an organization that could eventually provide an alternative to a radio distribution system managed by NPR.

“When I came into this organization, we talked about the first 50 years of public media and the next 50 years,” Ms. Maher said in the interview. “Nobody expected there to be quite as fine a point on it as this moment in time.”

‘She Had Done Her Homework’

Running NPR is a notoriously difficult job. It’s one part politician, managing relationships with hundreds of stations; one part turnaround artist, trying to expand a business with roots in traditional radio; and one part fund-raiser, appealing to foundations and other donors. And NPR’s most important product is its journalism, which its chief executive has no direct control over.

Further complicating matters: NPR is a nonprofit with a majority of its board of directors from local stations, who occasionally have diverging interests.

Over the last 15 years, NPR has had seven chief executives.

NPR’s board members were excited in the fall of 2023 when they found Ms. Maher. She had worked for the World Bank and HSBC. As the chief executive of the nonprofit that runs Wikipedia, she oversaw a sprawling, complicated community of volunteer editors. And she was prepared.

“She had done her homework,” said Jennifer Ferro, the former chair of NPR’s board who led the search committee.

In some ways, Ms. Maher was an unusual pick. She had no experience running a professional news organization. And unlike NPR’s recent top leaders, who were media executives in the twilight of their careers, Ms. Maher was relatively young and knew the tech world. She was also telegenic, eventually breezing through interviews with late-night hosts like Stephen Colbert and Jordan Klepper. (“I barter these for groceries,” she said, presented with a “Daily Show” tote bag.)

During one of the most consequential times in NPR’s history, Ms. Maher has been a highly visible C.E.O., holding conference calls with station leaders and delivering direct-to-camera fund-raising appeals.

Clad in bright blazers and sprinkling tech argot into her conversations, Ms. Maher has been crisscrossing the nation to visit NPR’s stations, with recent trips to Bloomington, Ind., and Thousand Oaks, Calif. (“It’ll take me five years to get to all of them,” she said.) While she is out on maternity leave, NPR’s chief financial officer, Daphne Kwon, will fill in as interim president.

In early April 2024, two weeks after she started, Ms. Maher and NPR faced an unexpected crisis. Uri Berliner, a senior editor at NPR, published an essay in The Free Press accusing the network of a liberal bias in its news coverage.

The crisis deepened a week later. Chris Rufo, the conservative activist who ran social media campaigns against figures including Claudine Gay, the former Harvard president, circulated years-old social media posts from Ms. Maher that criticized Donald J. Trump and supported liberal causes. (“Also, Donald Trump is a racist,” read one.)

NPR’s critics seized the moment. In early May, Republicans in Congress called on Ms. Maher to testify on allegations of bias. Compounding the situation: Some at NPR were surprised by Ms. Maher’s social media posts; she told The Times that the board hadn’t asked her about them before she was hired.

Steve Inskeep, a host of “Morning Edition,” published a rebuttal to Mr. Berliner’s essay, accusing him of errors. NPR noted in a statement that Ms. Maher wrote her posts before she joined the news industry.

Did she consider quitting? “I really don’t like bullies,” she said. She remembered thinking, “My view is that the overall goal of what I was brought in to do was far greater than that five-week mark.”

Ms. Ferro, who was in touch with Ms. Maher frequently during that period, was determined to keep her at NPR. She was the right leader, she said. And she believed getting rid of an executive because of political pressure 40 days after she joined would only weaken the organization.

The furor surrounding her posts subsided. But they would come up again a year later.

An ‘Asteroid’ Looms

In November 2024, weeks after President Trump was elected, an ominous memo on the impact of federal defunding written by two public media leaders began circulating among station directors. It raised the possibility that Congress could eventually claw back all funding for NPR and PBS.

“This is a scenario akin to an asteroid striking without warning,” the report said. It included a diagram showing that money from Congress is allocated to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which then doles it out to NPR, PBS and local stations across the United States.

For NPR and PBS, defunding would be survivable. Most of NPR’s revenue comes from membership dues, sponsorships and donations. But for local stations, many of which rely on the Corporation for Public Broadcasting for a majority of their budget, this was catastrophic.

In March, Ms. Maher and Paula Kerger, the chief executive of PBS, were called to testify before Congress in a hearing whose title seemed to presage its conclusion: “Anti-American Airwaves: Accountability for the Heads of NPR and PBS.”

The hearing was predictably divided along partisan lines. The Republicans, who argued that NPR and PBS were outmoded, a waste of taxpayer money or liberally biased, interrogated Ms. Kerger and Ms. Maher, asking the NPR chief executive about her social media posts and the network’s coverage of Hunter Biden’s laptop. The Democrats praised NPR and PBS and mocked the proceedings (“Is Elmo now, or has he ever been, a member of the Communist Party?”).

The hearing made it clear that Republicans in Congress, which had tried to pull NPR’s funding for a half-century, might finally make good on their threat.

‘How Big of a Cut Could We Tolerate?’

In April, as Congress was gearing up to claw back funding from the public media system, America’s Public Television Stations, an influential nonprofit advocacy group, sent a document to leaders of NPR, PBS and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

The document listed several scenarios that might allow NPR and PBS to save funding for local stations by agreeing to give up money for national programs. It even included a “save-face rationale” for some Republicans in Congress who wanted to justify their support of public media.

“How big of a cut could we tolerate?” the document asked.

At a meeting soon after, Ms. Kerger and Ms. Maher expressed support for such a compromise. It seemed, briefly, like the heaviest hitters in public broadcasting were on board with the plan.

But there were also signs of major strain.

On a call this spring, Patricia Harrison, the chief executive of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, asked Ms. Maher whether she would be willing to say anything to members of Congress or the press to acknowledge concerns from listeners who viewed NPR’s reporting as biased, according to two people familiar with her remarks.

Ms. Maher rebuffed that suggestion. She didn’t believe that NPR was biased, and she thought saying so would undermine the organization and fail to placate those who were critical of the network, according to a person familiar with her thinking. After she refused, months of simmering tension between the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and NPR came to the surface. Ms. Harrison told Ms. Maher she should resign her position for the good of public media.

Things got more tense when, on May 1, Mr. Trump issued an executive order banning government funding of NPR and PBS. NPR sued the White House, arguing that the order violated the Constitution. And it added the Corporation for Public Broadcasting as a defendant, since Mr. Trump’s order directed it to deny NPR funding.

NPR also changed its position on the funding compromise: It now viewed any cuts as a violation of the First Amendment, essentially arguing that cuts amounted to government discrimination against NPR based on its viewpoint.

Ms. Maher said that once the Trump administration attempted to tie the organization’s ability to receive federal funding to its editorial decisions, the compromise “was no longer an option.”

In July, the Senate officially voted to defund public media, 51 to 48. In a somber meeting with employees days after the vote, Ms. Maher said NPR and its member stations had waged a “David-and-Goliath-style” fight that included 191 meetings during a trip to Washington, D.C., 40 of which were directly with elected officials.

“We put up a really good fight as a team, as an organization, as a network, and we should be damn proud of it,” she said. She also appeared in a fund-raising appeal from NPR. “We need your help,” she said. Donations poured in.

Then the Corporation for Public Broadcasting took a step that ratcheted up tension with NPR. For years, the corporation had funded a radio distribution system managed by NPR.

Instead, in September, it announced it was awarding a major grant to Public Media Infrastructure, the new entity formed by a group of five public media organizations including WNYC, PRX and the Station Resource Group.

After that, the legal battle between NPR and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting erupted.

‘Mom and Dad Are Fighting’

In late September, NPR’s board of directors gathered on a video call to discuss a highly unusual move championed by Ms. Maher: seeking a restraining order against public radio’s biggest supporter.

The situation was complicated. NPR had already sued the Corporation for Public Broadcasting alongside the Trump administration, but the restraining order went a step further. In court, NPR would argue that the Corporation for Public Broadcasting had changed its mind about funding a radio distribution system managed by NPR because Mr. Trump issued his executive order in May — essentially helping him violate the First Amendment. The restraining order sought to keep the funding from going elsewhere.

The corporation, for its part, argued that it had funded the new entity because NPR had a monopoly over its radio distribution grants, and it wanted those efforts to be more independent. It also told a judge it was acting on an independent recommendation that predated the funding fight.

At stake were millions of dollars and the possibility of widening the rift between NPR and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. As one public media executive put it at the time: “Mom and Dad are fighting.”

In the end, only three members of NPR’s 23-person board of directors voted against the restraining order or abstained from voting. Ms. Maher had rallied the board with an impassioned speech about the importance of standing firm on First Amendment issues.

The legal action inflamed a painful internecine battle, as emails from NPR and the corporation became public in discovery. “There is a dream scenario — we get the money and CPB goes away by the action of Congress,” wrote one NPR executive, referring to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, in April.

In one email, an executive with the Corporation for Public Broadcasting suggested that the organization hadn’t funded an NPR project because of the “political challenges” that came with doing so, although they couldn’t “own it” in public.

In November, the two sides reached a settlement, with the corporation agreeing to direct some of its remaining funding toward the satellite system managed by NPR and declaring Mr. Trump’s executive order unconstitutional. Both sides issued statements declaring victory, with NPR citing a judge’s remarks stating that the organization had made a “very substantial showing” to support its argument.

In tandem with the settlement, Ms. Maher decided that NPR would give stations relief on some of their fees, earning her some goodwill among station managers across the country.

But a bigger chunk of money was never coming back. The Corporation for Public Broadcasting is scheduled to wind down in January.

‘You Have to Make a Decision’

Though the public broadcasting system is reeling, NPR’s business remains stable. Ms. Maher said NPR was expected to generate record donations this year and would deliver $22 million in financial support to members of its network, which has around 200 newsrooms. (Local stations’ fund-raising has also increased.)

While web traffic to NPR.org has declined this year, according to Comscore, a spokeswoman for NPR said the network’s total digital reach was up, factoring in platforms like YouTube, where NPR’s Tiny Desk concerts are popular. And NPR’s broadcast audience has increased roughly 8 percent this year, according to Radio Research Consortium.

The end of government support has raised questions about the future of public radio, with some stations choosing to disaffiliate with NPR and PBS entirely. Ms. Maher borrowed an analogy from a station manager, comparing public broadcasters to a family that now has to figure out where to host Thanksgiving after the loss of a parent.

“Now you have to make a decision as a family: Do you still want to come together every year for the dinner party?” Ms. Maher asked."